Autor: Jean-Michel Arnal, intensivista jefe del Hôpital Sainte Musse, Toulon, Francia

Fecha: 19.10.2018

Last change: 09.09.2020

FormattingUn estudio fisiológico reciente pone de manifiesto que la presión esofágica permite estimar la presión pleural en la región central del tórax en todos los niveles de PEEP. Por tanto, una medición absoluta de la presión esofágica resulta útil a la hora de establecer la PEEP y de monitorizar la presión transpulmonar.

Entonces, ¿cómo se mide la presión esofágica correctamente?

El globo esofágico debe colocarse e inflarse de forma adecuada, y su colocación debe verificarse.

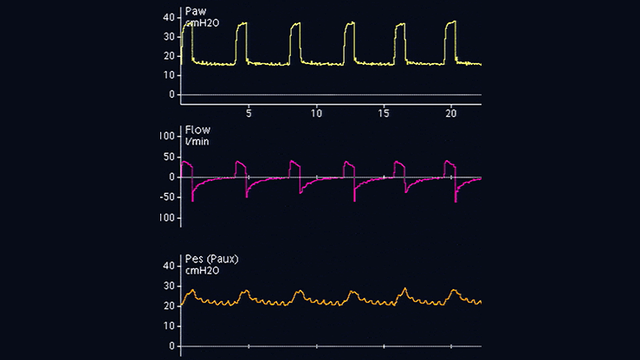

La colocación óptima del globo esofágico es el tercio inferior del esófago, a una distancia de 35–45 cm de las fosas nasales. Con un paciente en posición parcialmente decúbito, el globo vacío se introduce en el estómago, que está a unos 50–60 cm de las fosas nasales. El globo se infla a un volumen estándar (1 ml con un catéter CooperSurgical y 4 ml con un catéter Nutrivent). La presión gástrica muestra un desvío positivo durante la inspiración en pacientes con respiración tanto espontánea como pasiva. La colocación gástrica se determina ejerciendo una suave compresión epigástrica manual, que produce un aumento inmediato de la presión gástrica (consulte la figura 1).

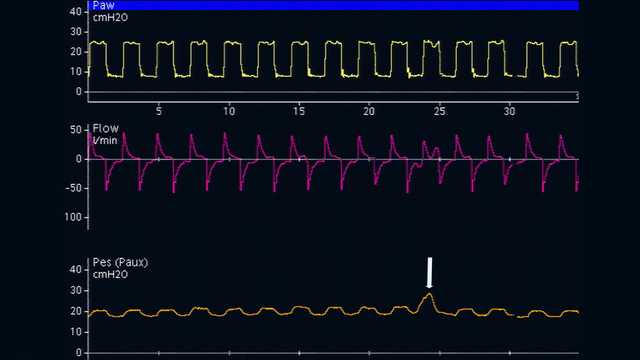

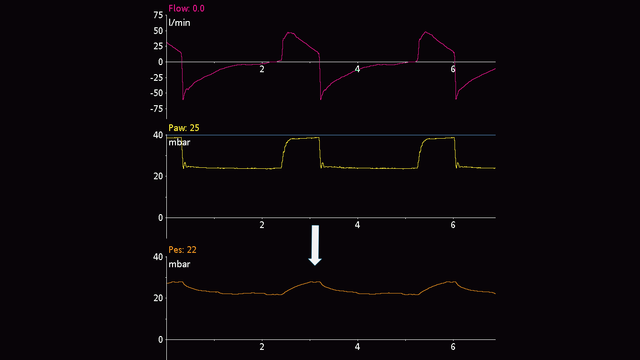

A continuación, el catéter esofágico se va retirando suavemente mientras el globo se infla, lo que ayudará a colocar el globo en el tercio inferior del esófago. Durante el cambio de presión gástrica (consulte la figura 2) a esofágica (consulte la figura 3), la línea de referencia de la forma de onda de presión cambia y aparecen oscilaciones cardiacas.

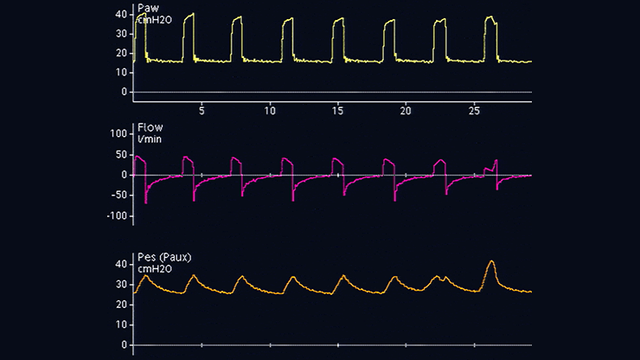

Los desvíos en la presión esofágica son positivos durante la inspiración en los pacientes pasivos (consulte la figura 4), pero negativos en el caso de los pacientes con respiración espontánea (consulte la figura 5). Si se producen oscilaciones cardiacas que distorsionan la señal de presión esofágica, el catéter se puede retirar unos 2–5 cm más.

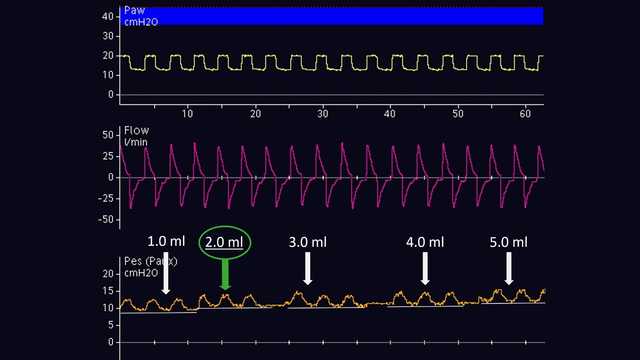

El volumen de aire para lograr el inflado adecuado del globo se debe valorar individualmente. Esto solo es posible en los pacientes pasivos. Según el método propuesto por Mojoli et al (2016), el globo se infla entre 0,5 y 3 ml a intervalos de 0,5 ml con un catéter CooperSurgical, y entre 1 y 8 ml a intervalos de 1 ml con un catéter Nutrivent (consulte la figura 6). Durante el inflado progresivo del globo, la línea de referencia de la presión esofágica aumenta y la magnitud del desvío de la presión esofágica cambia. El volumen de inflado adecuado es el que está asociado al desvío más pronunciado de la presión esofágica. Si dos volúmenes distintos muestran la misma magnitud de desvío de la presión esofágica, se seleccionará el volumen más bajo.

Una vez que el globo está correctamente colocado en el esófago y se ha inflado, se debe realizar una verificación mediante una prueba de oclusión. El principio consiste en cerrar las vías aéreas al final de la espiración para cambiar la presión en estas y, luego, confirmar que la presión esofágica cambia en la misma medida.

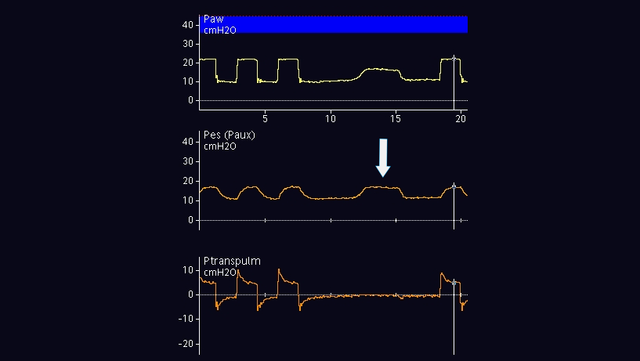

En los pacientes con respiración pasiva, se puede efectuar una oclusión al final de la espiración. Cuando la válvula espiratoria se cierre, ejerza una presión manual externa en la caja torácica, a ambos lados del pecho, para ver un desvío positivo de las presiones en la vía aérea y esofágica. La magnitud del aumento de las presiones en la vía aérea y esofágica debe ser la misma. Dicho de otro modo, la presión transpulmonar debe permanecer inalterada (consulte la figura 7).

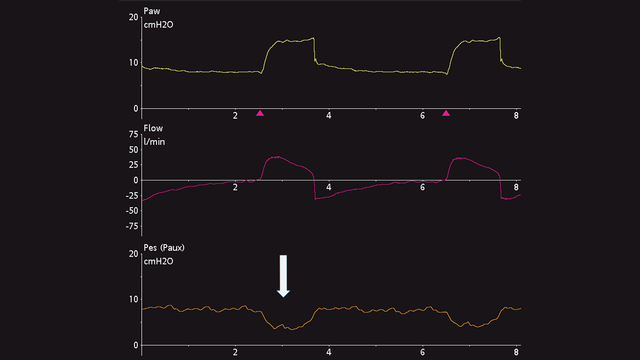

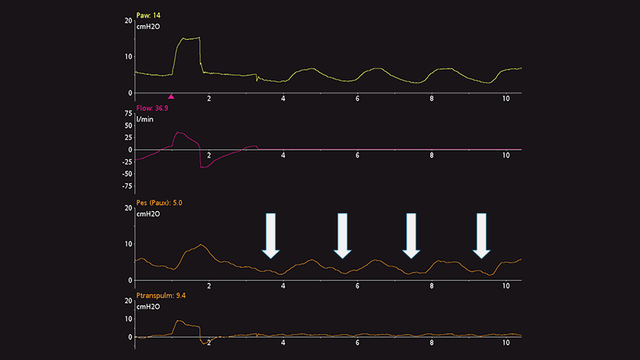

En los pacientes con respiración activa, la prueba de oclusión dinámica también emplea una oclusión al final de la espiración. No es necesario ejercer ninguna presión manual sobre el tórax, ya que el paciente realizará el esfuerzo inspiratorio espontáneo durante la oclusión. El resultado es un desvío negativo de las presiones en la vía aérea y esofágica. La magnitud de la reducción de las presiones en la vía aérea y esofágica debe ser la misma, esto es, la presión transpulmonar debe permanecer inalterada (consulte la figura 8).

Si desea monitorizar la presión esofágica constantemente, es importante reevaluar la correcta colocación y el volumen de inflado.

Puede consultar las citas completas a continuación: (

Recomendaciones probadas clínicamente sobre qué hacer y qué evitar a la hora de usar la medición de la presión esofágica en pacientes con SDRA.