Author: Munir Karjaghli, Clinical Applications Specialist, Hamilton Medical AG

Date of first publication: 15.11.2021

片肺換気中の人工呼吸には3つの目標があります。それは、(I)二酸化炭素除去を助ける、(II)酸素化を維持する、(III)術後の肺機能不全を低減する、です。片肺換気中の最適な人工呼吸戦略を決定するためにさまざまな研究が行われています。

周術期ALIには多くの異なる要因が寄与する可能性があります。肺傷害は、炎症性または生化学的要因に加えて、過拡張、過灌流、周期的リクルートメント/デリクルートメントによる機械的応力にも起因します。胸部手術を受けた患者では、「マルチヒット」理論により、手術関連要因、片肺換気、基礎疾患および併存疾患、過去の治療、その他の不特定事象の組み合わせによってALIの起こりやすさが高まる可能性があることが示唆されています(

胸部手術中および術後の片肺換気は、容量損傷、圧損傷、無気肺損傷、酸素中毒のリスクを高めます。これらはすべて、人工呼吸器誘発肺傷害を引き起こす重篤な合併症です(

片肺換気の管理について、臨床転帰の観点からある特定のアプローチを特に支持するデータはほとんどありません。何を保護的片肺換気とみなすかという定義は、主に専門家の意見、一般手術患者での両肺換気から収集されたエビデンス、および少数の臨床試験の影響を受けます。たとえば、一回換気量を片肺換気中の肺傷害に寄与する単一の要因として特定することは非常に困難です。今日まで、片肺換気中に呼気終末陽圧(PEEP)(

肺がん手術において片肺換気中にVTの低減、PEEPの増加、人工呼吸器圧力の制限、リクルートメント手技などの肺保護換気プロトコルを実施した後に行われたある後ろ向き研究では、急性肺傷害のリスクが低かったことがわかりました(

Society for Translational Medicineが発行した肺葉切除を受ける患者の人工呼吸管理に関する臨床実践ガイドラインでは、片肺換気の現在のエビデンスに基づいて推奨事項が提案されています(

すべてのHamilton Medical人工呼吸器で使用可能なアダプティブサポートベンチレーション®(ASV®)モードは、片肺換気で推奨される一回換気量とドライビングプレッシャーに準拠した肺保護戦略を自動的に実行します。さらに、完全にクローズドループモードのINTELLiVENT®-ASV (

Weilerらの研究によると、ASVは、片肺換気の状況が非常に変わりやすい場合でも患者を安全に換気できます(

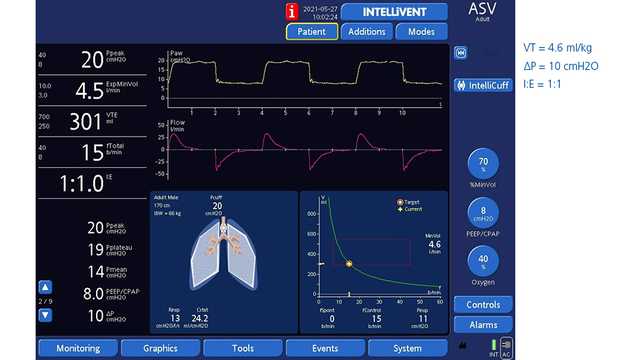

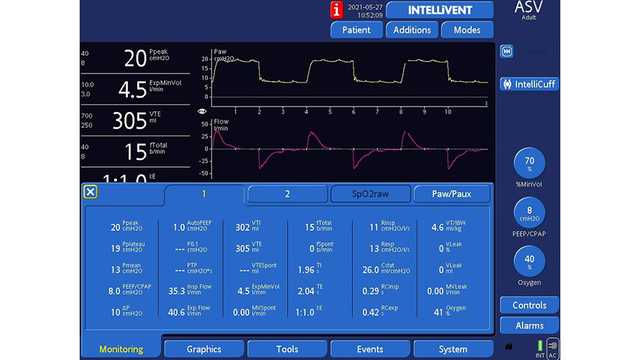

図1と2は、ASVで換気を受けながら右肺全摘術を受けた61歳の男性患者を示しています。

参考文献は下記をご参照ください。(