Autor: Karjaghli Munir, Respiratory Therapist, Hamilton Medical Clinical Application Specialist

Data da primeira publicação: 01.03.2024

Descubra tudo o que precisa saber no nosso guia sobre ventilação VNI: desde a abreviatura médica até o que é ventilação não invasiva, quando utilizá-la, como selecionar a interface e as configurações, e muito mais.

A ventilação não invasiva é comumente referida como VNI.

O termo ventilação não invasiva de pressão positiva (abreviado por NPPV ou NIPPV) foi previamente usado para distingui-la da ventilação não invasiva de pressão negativa, mas dada a raridade desta última atualmente, o termo mais simples VNI é mais conveniente. Uma vez que atualmente existe uma variedade de respiradores disponíveis para VNI, o uso do nome do produto BiPAP (Pressão positiva nas vias aéreas em dois níveis) como termo genérico para VNI deve ser evitado.

Outras abreviações são explicadas diretamente no texto.

A ventilação não invasiva de pressão positiva envolve o fornecimento de oxigênio para os pulmões através de pressão positiva sem necessidade de intubação endotraqueal. Esta é usada tanto na insuficiência respiratória crônica quanto na aguda, mas exige a monitorização e titulação cuidadosas, de modo a garantir que é bem-sucedida e a evitar complicações (

Ao longo do último século, a ventilação não invasiva (VNI) teve grandes melhorias e tem sido usada para tratar a insuficiência respiratória de várias etiologias. Provou-se que ela é mais eficaz na prevenção da intubação em comparação com tratamento de oxigênio padrão no contexto agudo (

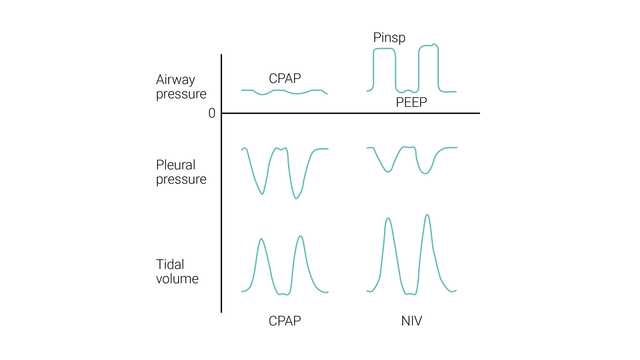

O suporte respiratório pode ser fornecido usando dispositivos de pressão positiva contínua nas vias aéreas (CPAP) ou aqueles que fornecem pressão positiva nas vias aéreas em dois níveis (ventilação com suporte de pressão, PSV). Para fins deste artigo, o nome VNI abrange tanto CPAP quanto PSV (

Podemos dividir os objetivos e benefícios da VNI no contexto de cuidados a longo prazo e agudos, da seguinte forma.

Benefícios da VNI em ambientes de cuidados agudos (

Benefícios da VNI em ambientes de cuidados a longo prazo (

O funcionamento da ventilação não invasiva consiste em criar pressão positiva nas vias aéreas, ou seja, a pressão fora dos pulmões é maior do que a pressão dentro dos pulmões. Isto faz com que o ar seja forçado a entrar nos pulmões (pelo gradiente de pressão), diminuindo o esforço respiratório e reduzindo o trabalho respiratório.

Ela também ajuda a manter o tórax e os pulmões expandidos, aumentando a capacidade residual funcional (a quantidade de ar que permanece nos pulmões após a expiração) após a expiração (corrente) normal; este é o ar nos alvéolos disponível para a troca gasosa (

Os modos seguintes são não invasivos:

CPAP tem como objetivo fornecer um nível contínuo de pressão positiva ao longo das fases inspiratória e expiratória de respiração.

Melhora a oxigenação, abrindo as vias aéreas colapsadas, melhorando a capacidade residual funcional (CRF) e melhorando a pré-carga e pós-carga no edema pulmonar cardiogênico (

CPAP melhora a complacência pulmonar e, portanto, reduz o esforço necessário para respirar, evitando o colapso alveolar e neutralizando a PEEP intrínseca excessiva observada em condições obstrutivas dos pulmões, como a DPOC (

A ter em conta: Se ΔPsuporte / ∆Pinsp for zero em VNI e VNI-ST, o respirador funcionará como um sistema comum de CPAP.

VNI (PSV) tem como objetivo fornecer dois níveis de suporte de pressão positiva nas vias aéreas. O nível menor é semelhante a CPAP; no entanto, é mais frequentemente designada por pressão positiva no final da expiração nas vias aéreas (PEEP), pois está presente apenas na fase expiratória da respiração.

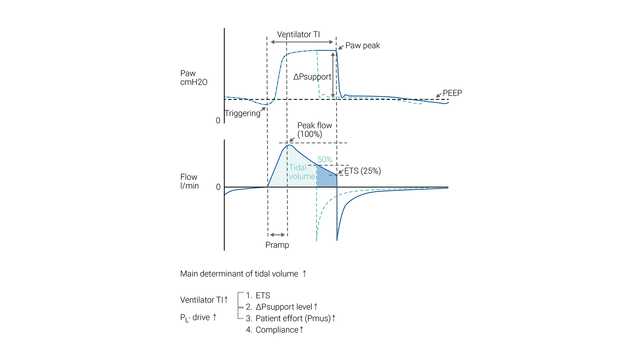

O esforço inspiratório do paciente é assistido pelo respirador em um nível predefinido de pressão inspiratória (ΔPsuporte). A inspiração é iniciada e alternada pelo esforço do paciente. Durante a VNI, o paciente determina a frequência respiratória, o tempo inspiratório e o volume corrente.

O tamanho do ciclo respiratório (volume corrente) gerado em um determinado paciente depende da configuração de ΔPsuporte — quanto maior for a configuração de ΔPsuporte, maior o volume corrente.

A ETS (sensibilidade de disparo expiratório) determina o tempo inspiratório espontâneo, alternando a expiração assim que o fluxo inspiratório diminuir para uma porcentagem pré-ajustada do pico de fluxo inspiratório.

Caso os critérios de ETS não sejam cumpridos (fuga), o tempo inspiratório também pode ser limitado por Ti máx (tempo inspiratório máximo).

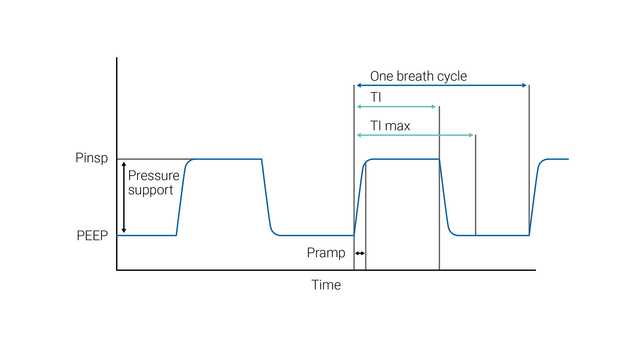

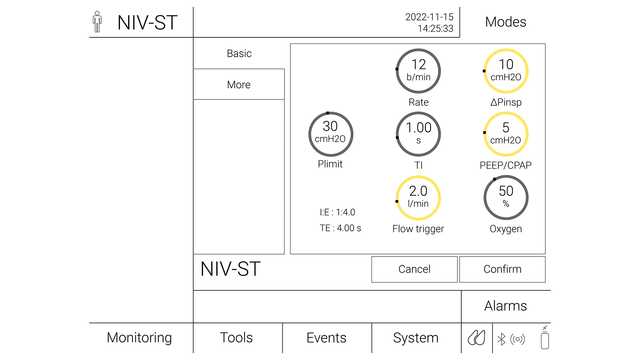

No modo S/T, o clínico configura a pressão inspiratória (∆Pinsp) e a pressão expiratória (PEEP), a frequência respiratória e o tempo inspiratório. O paciente pode iniciar ciclos respiratórios que são suportados até ao nível ∆Pinsp, como no modo VNI, mas se o paciente não fizer um esforço inspiratório em um intervalo definido (que é definido pela frequência respiratória definida), a máquina inicia a inspiração até ao nível ∆Pinsp definido. ∆Pinsp alterna, de seguida, para PEEP com base no período de tempo inspiratório.

A VNI-ST com a frequência de suporte é útil em caso de apneia ou ciclo respiratório periódico (

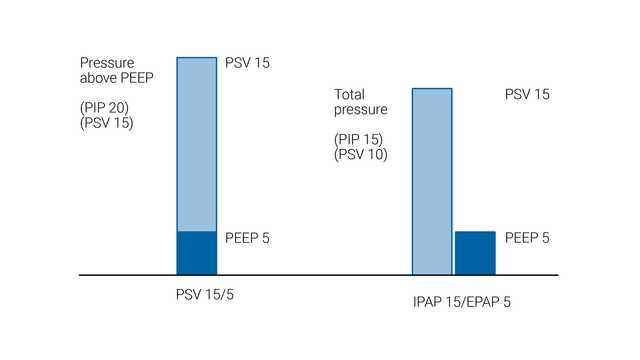

Os modos VNI e VNI-ST são tipos de ventilação não invasiva de pressão positiva. O suporte de pressão é geralmente considerado como sendo o mesmo que CPAP/BiPAP, exceto o fato de o suporte de pressão ser fornecido por um respirador e BiPAP ser fornecido por um respirador não invasivo.

Em VNI e VNI-ST, o nível de suporte de pressão é aplicado como pressão acima da PEEP de linha basal. No entanto, a abordagem é diferente com respiradores de dois níveis, em que a PIPVA (pressão positiva inspiratória nas vias aéreas) e a PEPVA (pressão positiva expiratória nas vias aéreas) são definidas. Nesta configuração, a diferença entre PIPVA e PEPVA é o nível de suporte de pressão.

De modo a minimizar o risco de falhas ou complicações, cada paciente deve ser avaliado corretamente quanto à sua adequação para receber a VNI com segurança.

As indicações para o uso da VNI incluem os pacientes com:

Os pacientes devem ser monitorados cuidadosamente durante as primeiras 24 horas após iniciarem a VNI, uma vez que este é o período com a maior taxa de insucesso do tratamento. Embora os pontos de dados na apresentação, como uma FR (frequência respiratória) alta, valores baixos de pH arterial ou PaO2/FiO2 baixa, possam ajudar a prever a falha, o indicador mais forte do insucesso do tratamento durante este período é a não demonstração de um melhoramento nestes parâmetros, 1–2 horas após o início do tratamento de VNI (

| Clinical indication | Certainty of evidence | Recommendation |

| Hypercapnia with COPD exacerbation | High | Strong recommendation for |

| Cardiogenic pulmonary edema (CPE) | Moderate | Strong recommendation for |

| Immunocompromised | Moderate | Conditional recommendation for |

| Post-operative patients | Moderate | Conditional recommendation for |

| Palliative care | Moderate | Conditional recommendation for |

| Trauma | Moderate | Conditional recommendation for |

| Weaning in hypercapnic patients | Moderate | Conditional recommendation for |

| Post-extubation respiratory failure | Low | Conditional recommendation against |

| Obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS) | Low | Conditional recommendation for |

| Neuromuscular disease and chest wall disease | Low | Conditional recommendation for |

| Prevention of hypercapnia in COPD exacerbation | Low | Conditional recommendation against |

| Post-extubation in high-risk patients (prophylaxis) | Low | Conditional recommendation for |

| De novo respiratory failure | No certain evidence | No recommendation made |

| Acute asthma exacerbation | No certain evidence | No recommendation made |

Absolutas:

Relativas:

(

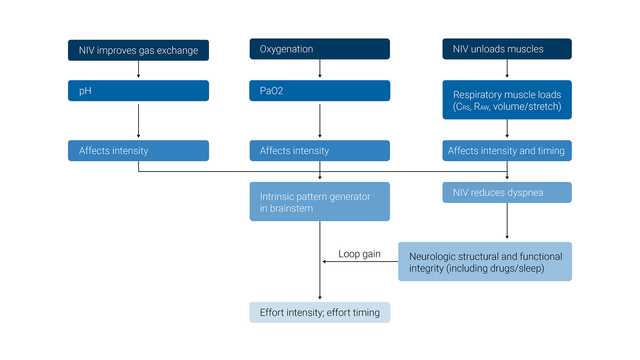

O principal efeito desejado da VNI é manter os níveis adequados de PO2 e PCO2 no sangue arterial e, ao mesmo tempo, aliviar a carga dos músculos inspiratórios.

Os efeitos fisiológicos da ventilação não invasiva são os seguintes:

(

(

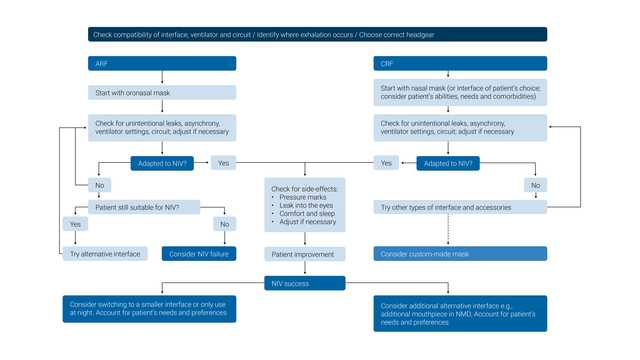

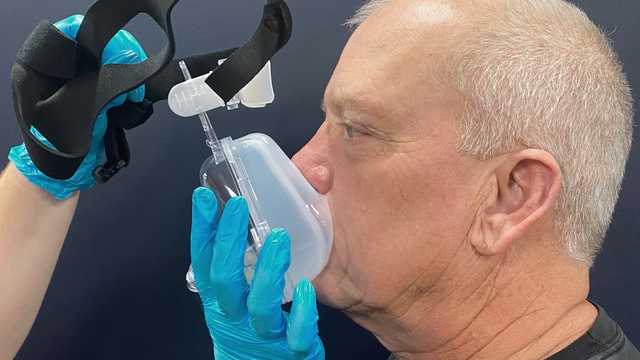

Selecione a máscara concebida para ser utilizada com um respirador de terapia intensiva (sem porta de fuga ou válvulas de arrasto).

O tamanho errado da máscara, o posicionamento incorreto ou uma vedação insuficiente da máscara podem causar desconforto ao paciente e ferimentos por pressão. É importante escolher uma interface que tenha o tamanho adequado para cada paciente, avaliar o ajuste e o posicionamento da máscara no rosto e reposicionar a máscara conforme necessário para minimizar fugas.

A ter em conta: As interfaces de VNI com válvulas de arrasto foram concebidas para respiradores não invasivos que usam um circuito de alça única. A válvula de arrasto é necessária para evitar a asfixia em caso de falha do respirador ou de desconexão do tubo. As máscaras com portas de fuga apenas devem ser usadas com respirador de circuito de alça única e não devem ser usadas com respiradores Hamilton Medical.

(

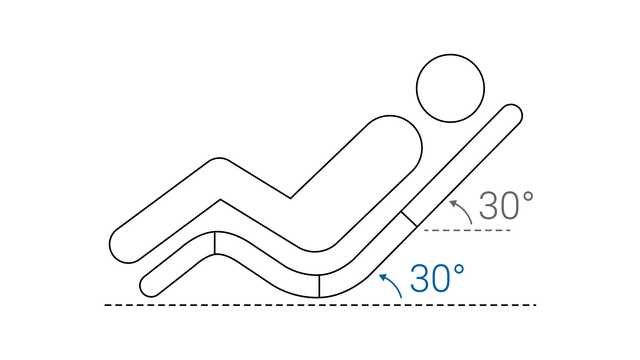

Recomendações (

A dispneia pode causar sentimentos de ansiedade e medo. Por isso, o profissional de saúde ou o paciente deve segurar a máscara no lugar ao aplicá-la pela primeira vez.

Desta forma, a máscara pode ser removida rapidamente se o paciente começar a entrar em pânico ou precisar comunicar. A estratégia de iniciar com pressões baixas pode ajudar os pacientes a se adaptar mais rapidamente à VNI.

(

Os alarmes de emergência são importantes para reconhecer a deterioração na condição do paciente e alertar a equipe nas seguintes situações:

(

O insucesso da VNI tem sido geralmente definido como a necessidade de intubação devido à inexistência de um melhoramento na gasometria arterial e nos parâmetros clínicos, ou morte (

Preditores de sucesso:

Preditores de insucesso:

Em um grande estudo de coorte prospectivo, a escala HACOR previu o insucesso da VNI após 1 hora de tratamento com alta especificidade (90%) e boa sensibilidade (72%) (

A sincronização do paciente com o respirador é uma questão importante que pode influenciar a eficácia e o sucesso da VNI.

O fenômeno mais comum é o disparo ineficaz (o esforço do paciente não é reconhecido pelo respirador; pode ser secundário à alta AutoPEEP ou à sensibilidade inadequada do disparo inspiratório), seguido pelo início espontâneo (fornecimento da pressão programada se não existir esforço do paciente) e pelo disparo duplo (fornecimento consecutivo de dois eventos de suporte de pressão programada em um intervalo de menos de metade do tempo inspiratório médio devido ao esforço continuado do paciente) (

A sincronização entre o paciente e o respirador deve ser verificada frequentemente. As assincronias podem ser detectadas observando o paciente fazendo perguntas simples a ele. O método mais prático deve ser a análise das formas de onda de fluxo e pressão (

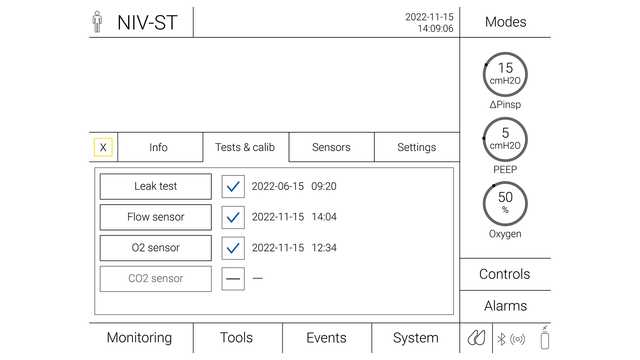

Os respiradores da Hamilton Medical oferecem uma funcionalidade para compensação de fuga, IntelliTrig, durante o ciclo respiratório completo para aumentar a sincronização do paciente com o respirador e reduzir o risco de início espontâneo. Usando o IntelliTrig, o respirador identifica a fuga medindo o fluxo na abertura das vias aéreas e usa estes dados para ajustar automaticamente o fornecimento de gás, mantendo, ao mesmo tempo, a resposta à sensibilidade de disparo inspiratório e expiratório ajustada.

Os respiradores Hamilton Medical também possuem um recurso opcional, IntelliSync+, que analisa continuamente formatos de formas de onda e que consegue detectar os esforços do paciente imediatamente e, de seguida, iniciar a inspiração ou expiração em tempo real (

Juntamente com nosso HAMILTON-C1, a solução compacta para ventilação não invasiva, todos os respiradores da Hamilton Medical oferecem a opção de VNI ( disponível no HAMILTON-C6, no HAMILTON-C3 e no HAMILTON-C1/T1/MR1).