Footnotes

- A. https://www.ecri.org/Resources/In_the_News/Sound_the_Alarm(PSQH).pdf

- B. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555522/

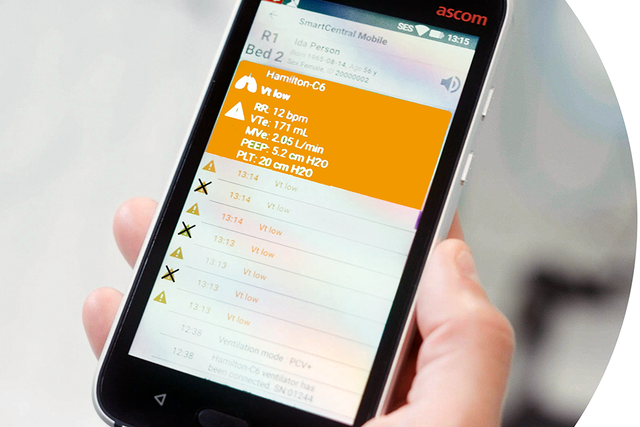

- C. Only available for HAMILTON-C6/G5/S1

References

- 1. Cvach M. Monitor alarm fatigue: an integrative review. Biomed Instrum Technol. 2012;46(4):268-277. doi:10.2345/0899-8205-46.4.268

- 2. McBride DL, LeVasseur SA. Personal Communication Device Use by Nurses Providing In-Patient Care: Survey of Prevalence, Patterns, and Distraction Potential. JMIR Hum Factors. 2017;4(2):e10. Published 2017 Apr 13. doi:10.2196/humanfactors.5110